5 Predictions for California's Zoning Holiday

The Builder's Remedy is the biggest change in zoning since, well, zoning

The Builder’s Remedy is the talk of the California land use world. Cities that fail to plan for their state-appointed growth targets lose the ability to deny certain projects based on their zoning code. Thousands of units are in the pipeline in SoCal. Dozens of Bay Area cities will be eligible for the Builder’s Remedy starting on Feb 1st, 2023, most likely including San Francisco.

We believe the Builders Remedy will have a big impact in the next few years in unlocking projects, while making cities create real plans to solve the housing crisis.

Here are five predictions, based on our conversations with dozens of developers, land use lawyers, and real estate investors.

Prediction 1: The builders are coming

Hundreds of developers will file Builder’s Remedy projects in 2023 as awareness spreads and more cities become eligible. YIMBY-Law is keeping track of city-by-city status.

The motivation for developers is clear. The SB 330 pre-application is simple to file and inexpensive. It gives the developer an option to pursue the zoning-optional project with a full application within 6 months, or use it as leverage to extract concessions for a zoning-approved project.

The clearest downside is the potential to damage the developer’s relationship with city staff. This risk looms large to repeat players in larger cities—think Tishman Speyer in San Francisco—but not to others.

An emerging tactic is to submit a legal letter alongside the SB 330 pre-app, explaining the developer’s intent to use the Builder’s Remedy. Multifamily developer Scott Choppin recently tweeted his letter as an example.

Scott’s project was somewhat unique in already completing CEQA in an earlier submission, which as you’ll see below, is a sticking point. Scott is not using Builder’s Remedy to bypass density constraints, but rather to bypass a broken discretionary approval process.

Prediction 2: CEQA is the fulcrum

CEQA is the California Environmental Quality Act. It was adopted in the 1970s, and envisioned as a way to ensure environmental protection in government decisions. Over decades of court decisions expanding the law’s scope, it’s been weaponized to block housing development in clearly suitable locations like Stevenson St. in San Francisco’s SoMa neighborhood.

Builder’s Remedy projects bypass zoning rules, but not CEQA. How developers navigate CEQA will separate projects into 3 buckets.

Bucket 1) Follow adopted plans for CEQA streamlining

California law requires both regions and cities to plan for future growth, and makes CEQA streamlining a carrot for developers to make the plans become a reality.

At the regional level, SB 375 (adopted in 2008) unified planning for housing and transportation infrastructure, with a goal of reducing greenhouse gas emissions from vehicle trips. Building dense housing close to transit is an obvious way to do this. SB 375 creates multiple CEQA streamlining options for qualifying projects. A full breakdown is available from SCAG.

The most developer-friendly exemption is for "Sustainable Communities Projects". These can qualify for full CEQA exemption if they meet a number of criteria, including a limit of 200 units and location within a 1/2 mile of a major transit stop. Meeting local zoning requirements is not one of the criteria, so Builder's Remedy projects should be able to take advantage of this exemption if they otherwise qualify.

At the city level, the Housing Accountability Act requires cities to identify exactly where future housing will be built in their General Plan, of which the Housing Element is a part. NIMBY cities will often use their General Plan to create a fantasy of future growth, knowing they can kill any proposed project via discretionary approvals in their zoning regs. Builder’s Remedy projects are immune to those discretionary approvals, suddenly making the city accountable to their General Plan. Sometimes dreams come true!

Being a discretionary process, adoption of General Plans are subject to CEQA. Therefore, cities bear the burden of preparing an EIR that covers all the housing proposed in the General Plan. This EIR can be leveraged to reduce CEQA scope for a developer proposing a specific project, down to project-specific significant effects which are peculiar to the project. This eliminates entire categories of CEQA scope, like traffic impacts, making the process more manageable.

Projects like this can actually be quite large, as cities have in many cases created very large allocations in their general plans. For example, look at 3030 Nebraska Ave, part of the wave of Builder’s Remedy applications in Santa Monica. The project proposes 2,400 units in 15 stories. It’s an upgrade from an earlier 190 unit proposal, which is covered in the just-submitted Housing Element (part of the General Plan), and close to a light rail stop.

Both regional and city level CEQA streamlining options are appealing, but a caveat applies. Every option includes at least some discretionary interpretation by a local agency. These ultimately roll up to a political body that can make bad faith arguments—got mountain lions?—or frivolous delaying tactics. By contrast, statutory and predictable CEQA exemption paths do exist, like those offered by AB 2011 or SB 35.

Bucket 2) Use the small infill exemption

CEQA has two exemptions for infill development: Class 3 and Class 32.

Class 32 has no unit limit, but projects must explicitly follow local zoning rules. Hence it's not a fit for Builder’s Remedy projects.

Class 3 is limited to 6 units in urban lots, and doesn’t rely on local zoning. This implies a 5-unit Builder’s Remedy project on a single family lot qualifies, with one affordable unit fulfilling the BR 20% affordable requirement. We believe there is an opportunity for small scale developers—and enterprising property owners—to take advantage of this exemption, which we’re calling BR-5 projects. These can fulfill the unmet intention of SB 9, the “end single family zoning” rule which has been bogged down by local regs.

As in Bucket 1, a city agency must still approve a Class 3 exemption request, so its not bulletproof. The eligibility language in CEQA is clear, but NIMBY cities are known to be creative in abusing CEQA to create delays.

We don't know of any Builder's Remedy project using this pathway yet. If you do, please let us know! We'd be excited to help, and we have some programs in the works.

Bucket 3) F*ck plans, go BIG

Builder's Remedy creates the option to ignore both zoning and the general plan, and propose lots of housing anywhere. This is a boogeyman scenario, almost guaranteeing a protracted CEQA battle. We think it’s unlikely such a project would come to fruition, but it’s possible for projects with enough margin. That can be enough to provide a developer with negotiating leverage in otherwise-stalled projects.

An example is the 2,300 unit beachfront project that drew national attention to Redondo Beach in September. The site of an aging power plant, the lot is zoned for public utility and park space. Prior attempts to rezone the site were shot down by public referendums. By using the Builder’s Remedy, the developer can just proceed directly to their project application.

Prediction 3: More housing is coming, no matter what

Most cities will adopt compliant housing elements to avoid Builder’s Remedy projects, laying the groundwork for future projects.

Santa Monica provides a compelling example. One can see their city council’s reaction to the Builder’s Remedy evolve in real time in their Oct 11, 2022 meeting. The context was whether to approve their staff-prepared housing element, which met state requirements to the chagrin of local NIMBYs.

Council member 1: Every day we don’t adopt [a compliant housing element], then more people get the opportunity to beat the clock with 15 story projects.

Council member 2: Has HCD said we’re stuck with these projects? 😳

City Staff: Yes. They sent us a letter from the housing accountability unit.

In other words, approving a compliant housing element will become a top priority for most California cities. As council member Brock describes later in the above video, local electeds will justify this to their NIMBY constituents with a simple question: “would you rather we had 15 story projects that can ignore zoning, like Santa Monica?”.

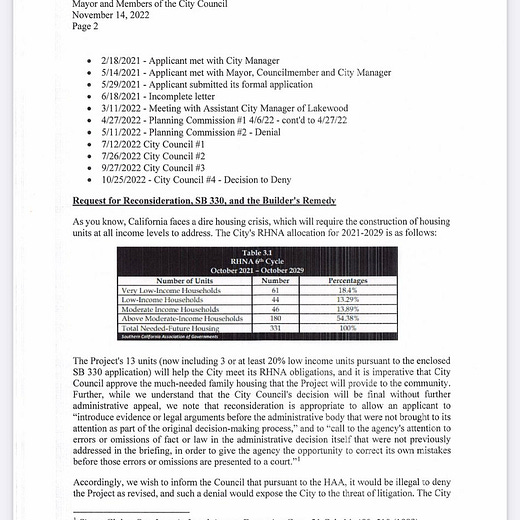

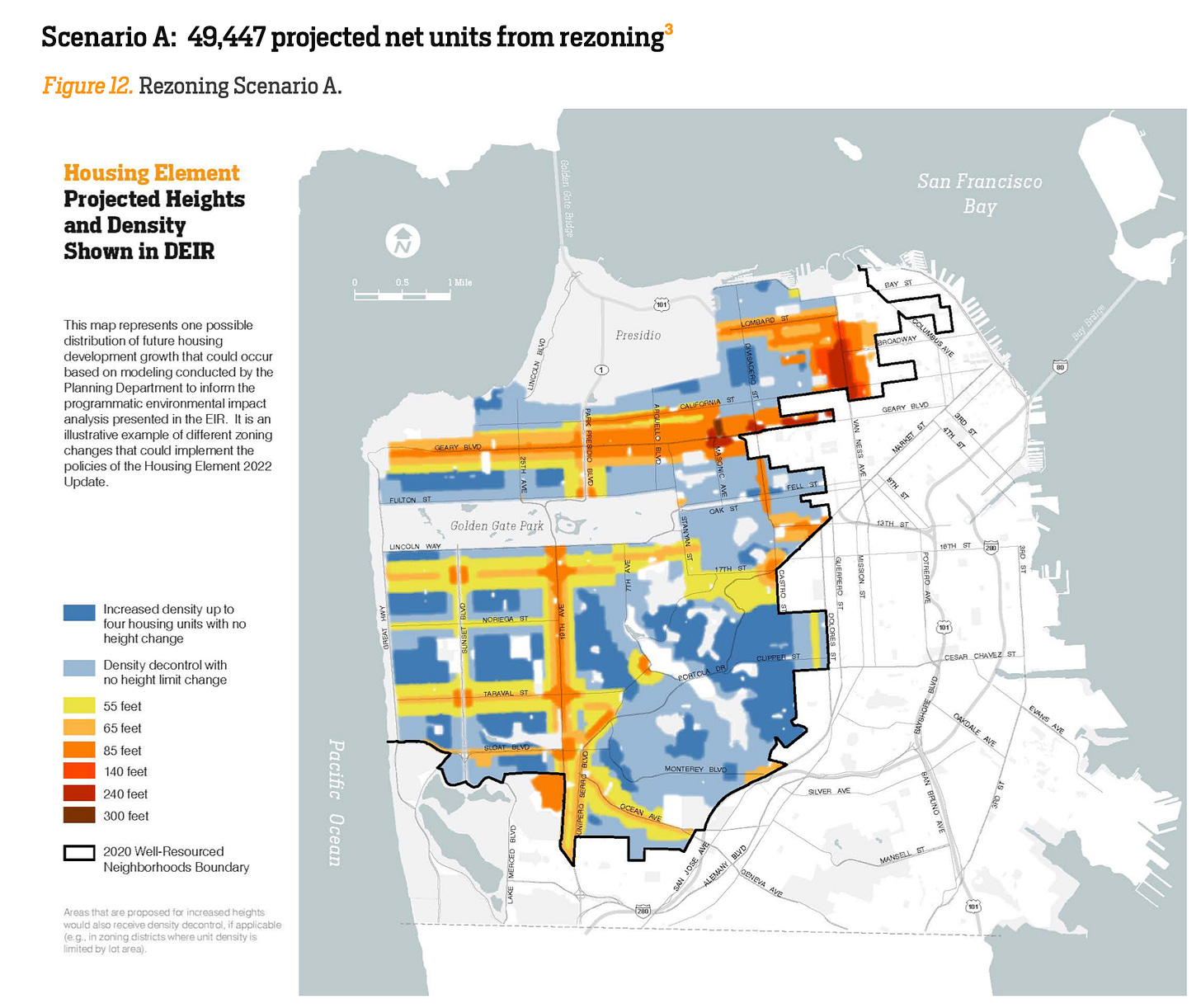

Unlike in past cycles, reaching compliance is a serious matter. It requires a viable, data-backed plan to reach RHNA targets turbocharged by SB 828. Cities that take the process seriously are making tough land use tradeoffs. That includes significant rezonings and other streamlining, like R-30 overlays in Encinitas and upzoning transit corridors in western San Francisco (pending approval).

Here’s a sub-prediction: After adopting compliant housing elements, most cities won’t keep up with their RHNA targets. This will open up multifamily lots to streamlining by SB 35 and related laws in the coming years. SB 35 exempts CEQA and subjective design reviews, and can be coupled to the state Density Bonus Law for density bonuses and allowances. (A note while we’re on SB 35. The labor wage requirements don’t apply for projects below 11 units. We’ve seen a lot of misreporting here.)

Even if the Builder’s Remedy isn’t used, it’s doing its job by forcing cities to accommodate growth instead of fighting it.

Prediction 4: There will be lawsuits

The Builder’s Remedy is yet untested in courts, but this will change.

Chris Elmendorf laid out the arguments that cities will use in denying projects. Appeals are expected to take years and reach the Supreme Court of California. We expect cases in the following areas.

Development standards. Projects are required to be “appropriate to, and consistent with, meeting the jurisdiction’s share of the regional housing need”. Can cities define “appropriate” as conforming to their zoning regs? A student of Chris firmly argues no.

Substantial compliance. Cities will argue that HCD’s determination of housing element compliance is not binding. Therefore a city can self-certify as compliant, following their self-serving reading of housing law, rendering Builder’s Remedy projects moot. For developers, the best way to avoid this ambiguity is to target cities with substantial gaps in compliance, like failing to submit a housing element at all.

CEQA delays. Cities are so used to abusing CEQA they now say the quiet part out loud: most CEQA delays are not about the environment at all, but rather about blackmailing developers to extract concessions for politically-engaged stakeholders. There are ongoing legislative and court efforts to reform this. If these efforts are successful, they will unlock Builder’s Remedy projects from the threat of CEQA purgatory.

Conclusion

2023 will be an exciting year for housing development in California.